What would a better legal brief look like? What would it be to submit writings for the judge’s consideration in ways that are more formally structured — so that these communications could:

1) be laid out systematically for the judge & her clerks (think in tables or side-by-side comparisons),

2) perhaps even made machine-readable (so that computers could process them and give the judge more ways to read/compare/index them), and

3) be composed by the lawyer/litigant in more straightforward ways (less laboring over blank pages in Microsoft Word, and more using universally accepted templates or forms).

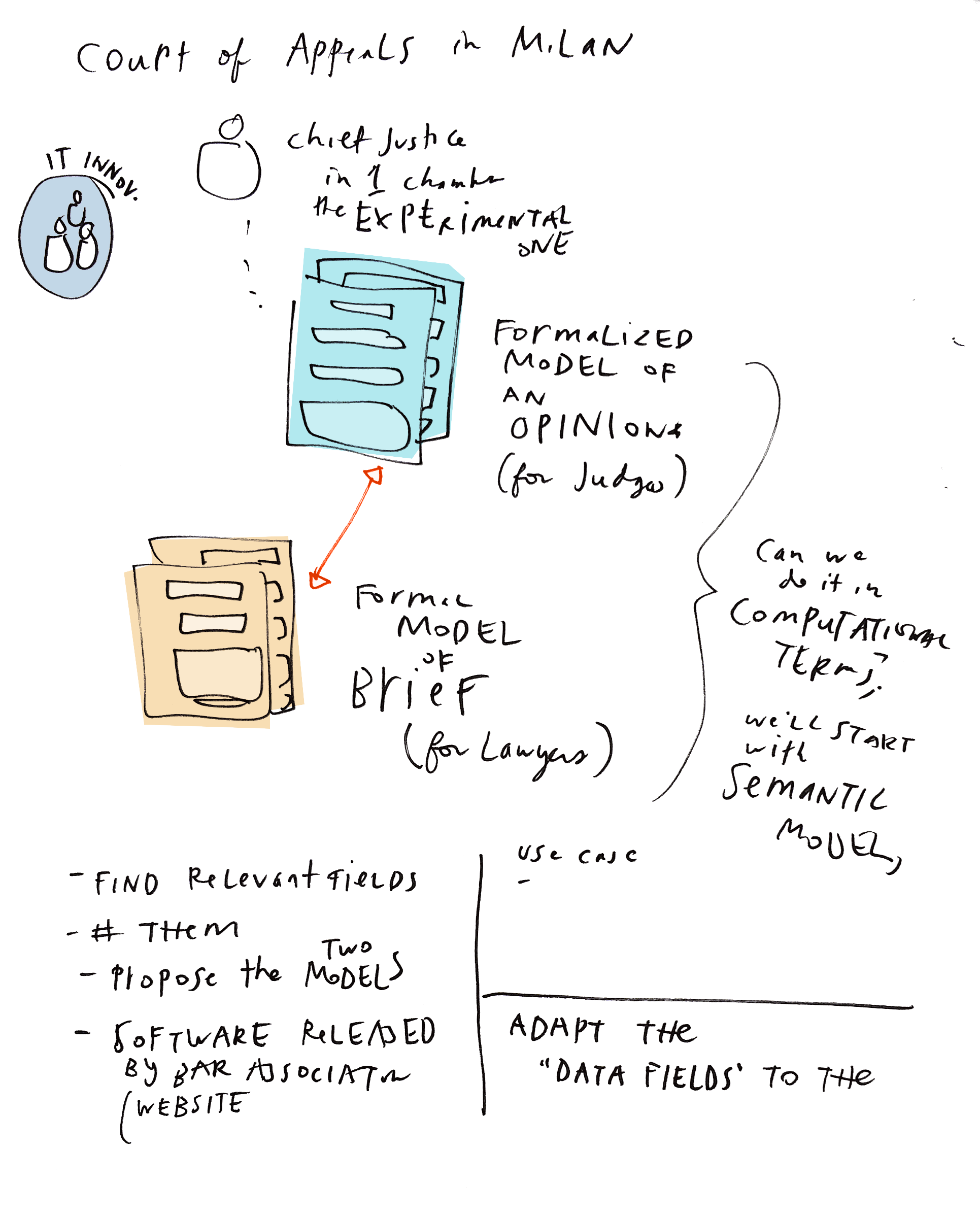

I’ve hinted at this possible redesign in earlier posts that one after a conversation with a clerk who wished that she could have tools to help her systematically compare & analyze opposing sides’ arguments. Now I’m picking up that conversation after speaking with an appeals court judge from Milan, Italy, who is exploring ways to formalize both judges’ opinions & lawyers’ briefs.

It isn’t the hardest redesign — it’s a matter of prototyping:

- what the key fields of information for a brief/opinion are

- how we can lay them out with prompts/questions in clear ways

- how to adapt the current ways of composing briefs & opinions into this new layout/model

- how we build tech tools that help us gather, process, and make these new briefs/opinions usable

The main thing to redesign, though, is the culture of practices. It’s a matter of changing what we think is legitimate as a legal submission or pronouncement — and how we as lawyers, clerks, and judges go about processing and composing information. This could be hard — but like the appellate judge in Italy proposes, it has a lot of value for the legal system to be more formalized & tech-enabled.

1 Comment

Part of the underlying problem may be that law schools tend to neglect and/or misunderstand legal skills. That said, the broad outline is simple, which I will now illustrate by reference to a dispute over how to interpret an ambiguous provision in a statute. The core components are these:

1. A statement of the elements and consequences of the legal rule that contains the ambiguity.

2. Identification of the element or consequences that contains the ambiguous provision.

3. Identification of the ambiguity in the element. This involves identifying the word or phrase that is ambiguous and identifying the possible meanings of this word or phrase.

4. Statement of the arguments that can be used for and against each meaning.

There is a final comment. One illustration of the neglect of legal skills in Australian law schools is that there is no attempt to explain to students the some of the common types of ambiguity. Indeed one can do a whole law degree without hearing even once the vital ‘A’ word.

Periodically some senior judge will jump up and down and complain that counsel do not know how to formulate an issue. As the good book aptly says: ‘As you sow, so shall you reap.’