Yesterday, I attended the Stanford Cyber Initiative’s event with California Attorney General Kamala Harris. It was about the AG’s office release of the 2015 Data Breach report. Much of the talk resonated with legal design: how to make privacy policies and other legal rules and terms around data privacy more accessible to lay users.

Here are my notes from the talk:

Privacy policies are impenetrable to most users — people don’t really read, there is not meaningful notice and consent through traditional privacy policies.

We live in a world with many new factors that increase the need for effective, usable privacy policies — because the gathering of data is at an unprecedented scale, and the risk of it being accessed by bad actors is increasingly high:

- More mobile usage, lots of data collection about so many things

- Internet of things, more devices connected to the Internet and potentially hacked

- Big data, huge amounts of data points gathered together and coordinated

- Sophisticated hackers, who can access devices and data sources, and use it in criminal activities

There are millions of data privacy breaches, affecting 49 million Californians are affected. Exponentially more consumers are being impacted — for their credit cards, social security numbers, and personal records. Physical breaches are going down in number — it’s malware and hacking.

Organizations need to sharpen their security skills, and put in more consumer protection. Let’s be smart, preventative and proactive. Here’s what can we do for Guiding Principles for 21st century privacy protection:

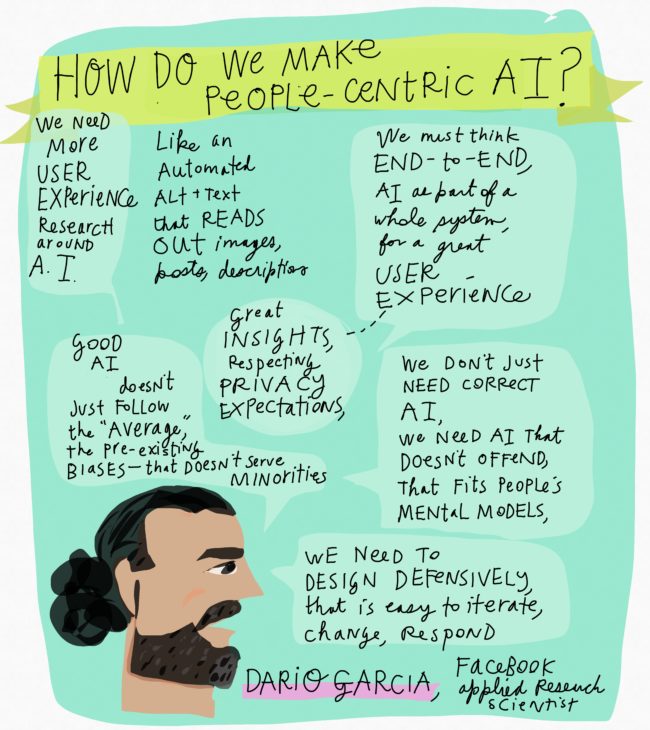

- Create user-centered privacy policies, they have to be helpful and informative – -not just a grand gesture. They are written by lawyers for lawyers. That is a problem. We need to apply the same creativity that goes into great websites that help people understand privacy implications — especially on the core issues that people really want to know.

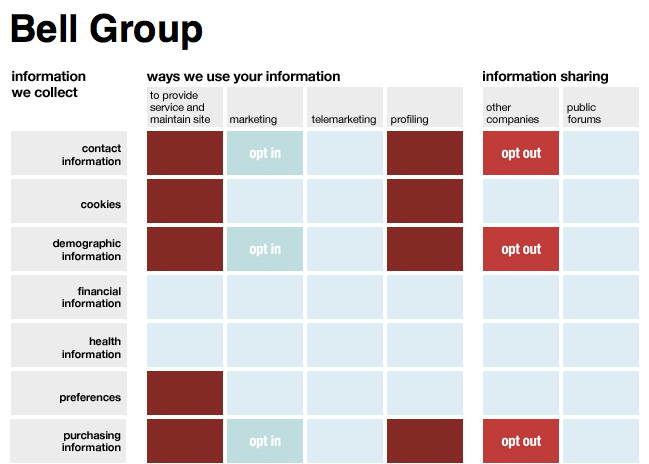

- Give consumers more control. They shouldn’t have all or nothing — there is gray space, so there should be more choices about what exactly is being tracked and when. The all or nothing approach to data collection is a false choice.

- Let’s improve the privacy settings default. As our devices travel with us, everywhere we go — let’s choose default settings that don’t expose users to risk. There should be opt-in for data collection, rather than opt-out.

- Ensure reasonable security. As the report outlines, there are minimum standards.

The government has the power to convene. Where the government invites industry — how do we solve this — the industry isn’t excited to come in but they do. There is a strong role for industry to play in solving this problem.

There need to be consequences and liability when people commit crimes. Perhaps it’s about more enforcement, in addition to public education.

“We in government” do not like to share our data. We hold on it, even when it’s not confidential and there is nonlegal need to hold onto it. Government is about public health, public safety, public welfare. We have so much data about it, and we could be using the data to make better policies around all of it. But the government holds on it, because they are afraid of transparency — people picking it apart. It makes the government vulnerable, and they don’t like to feel vulnerable.

The open data movement is about making these data sets more open, and collaborate with it. So researchers and journalists can test their hypotheses, find places there need to be new interventions, and where we stand it. We can approach intractable issues from non-ideological standpoints, be cold-blooded and unburdened by ideology. If we start to examine policies by data points and ROI, we can have more effective policy.

1 Comment

https://oag.ca.gov/breachreport2016