I attended a design talk where startup and tech companies’ designers were sharing notes about what they’ve learned about what kinds of visual and interaction design best connect with users. One of the designers mentioned that you have to sometimes throw out the “core principles of good design” for certain audiences. He was talking about lawyers.

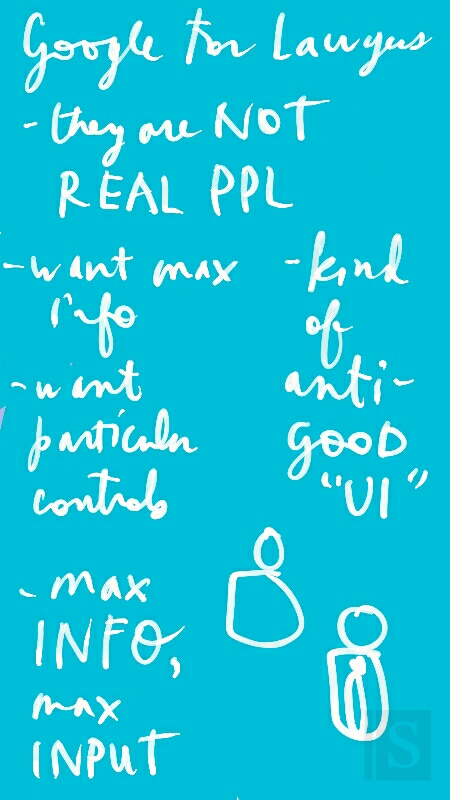

Before his current consumer-facing job, he had been working for a legal technology company about a decade ago. When their design team at the legal tech company was doing research about their target users — lawyers in law firms — they were shocked at what preferences they had. Essentially, lawyers wanted (or said they wanted) everything that designers have been trained not to want. The product the designer was trying to build was a “Google for Lawyers” and the lessons their user research was as follows:

- Lawyers want maximum overload of information in response to queries they do

- They want it listed out in detail, with lots of information packed onto the page

- They don’t want white space, they want text covering as much of the screen as can fit

- They want lots and lots of controls, all kinds of filters and sorting mechanisms

This is all anathema to “good design”, which says that instead, you should give users:

- A curated set of information that is displayed selectively and staged, so they can gradually dig into more

- Hide the details until a person has decided that they want to see them

- Give lots of white space for breathing room, don’t crowd the text

- Give a small menu of controls — the most commonly used and powerful ones — and bury others in ‘More options’, otherwise the user will be overwhelmed with choices

The question I have is, do lawyers really want the “bad design” or is it just that they have been only given bad designs and then convince themselves that this is what they prefer, and feel most empowered by? Does having all the information and controls always on the screen really help them be more efficient, knowledgable, and effective — or should designers/developers impose on them a cleaner, and more directed experience?

Thinking to the design of financial-professional-television programs, with so much text layered and scrolling over a central image, it seems this affinity for “bad design” is not just a legal professional issue.

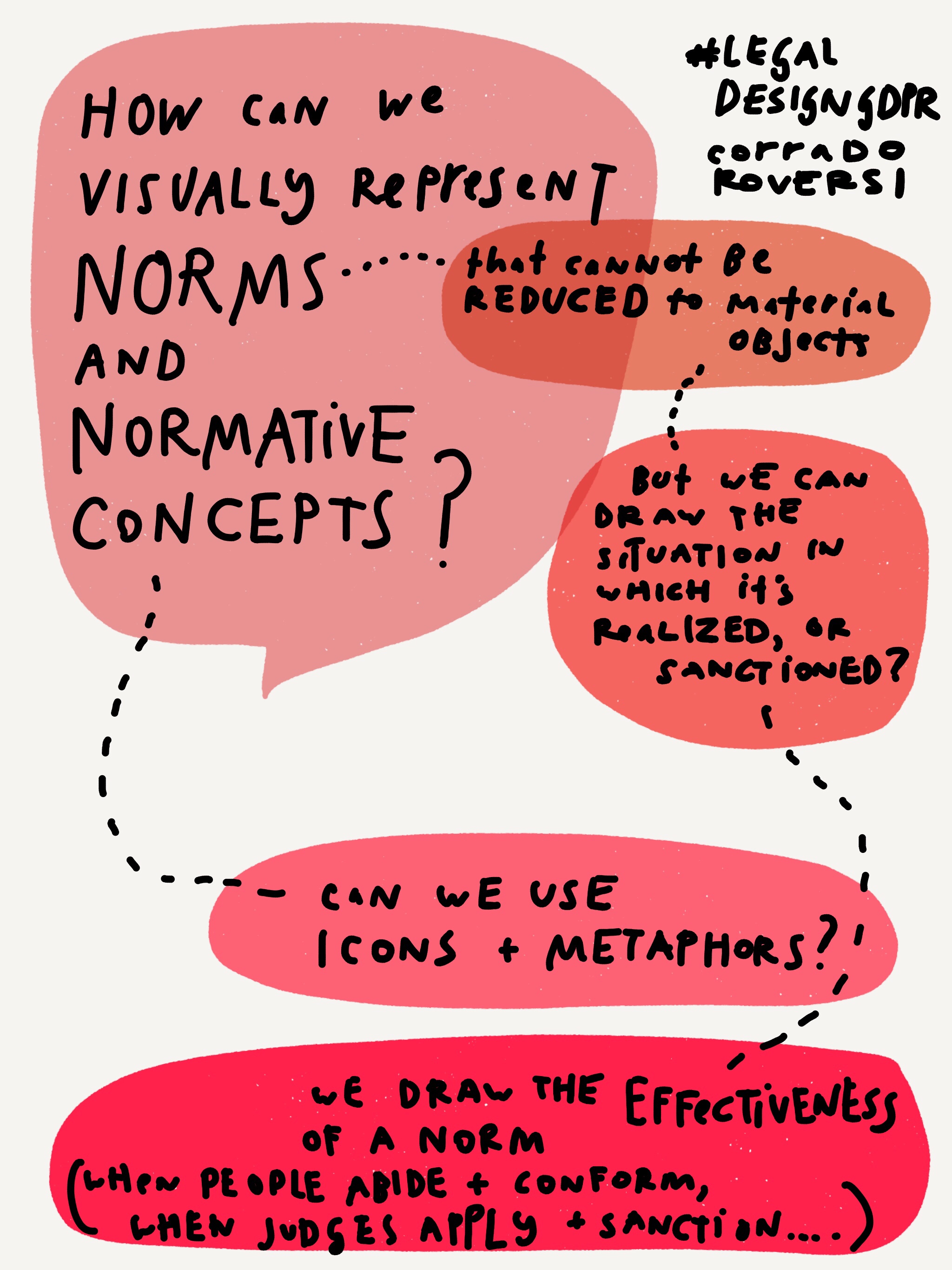

What would be interesting is empirical analysis, to see if the text-overload style of design does in fact improve lawyers’ ability to parse information, find the most relevant pieces of it, and use it intelligently — and to do it in an efficient and pleasant way. This could then be compared to a “good design” version of the same tool, to see if the white space and limited information/controls does prove to be a better tool and a better experience.

And of course underlying the design question is also the quality of the tool. If, for example, a Google for Lawyer tool does not have a strong algorithm underlying it, then perhaps it is better to give more info and controls to the professional, for them to make up for the parsing that the tool can’t do well.

Any thoughts? It’s interesting, if there needs to be a parallel (or perpendicular) set of what “good design” looks like when it comes to lawyers.

7 Comments

What we know to be good visual design is different from what lawyers are used to. And lawyers seem to be most comfortable with a) what they are used to and b) what they are expected to use. And in general these suffer from the things you mention. I think it is possible to shift conventions to employ better design principles but I think it will happen slowly for the lawyers. I’ve seen lawyers come around to appreciating good design but it takes time and and they need to see it work for them. I’d love to see the results of the test you mention. Makes me think of A/B testing. Sometimes the better design (according to the designer/team) is not always the one that works the best. Hard to argue against the data.

Hello Margaret

It is not so much that lawyers do not want good design, but they do not know good design until they see it. they are a bright bunch and soon catch on when they see their competitors producing smarter more client-friendly materials.

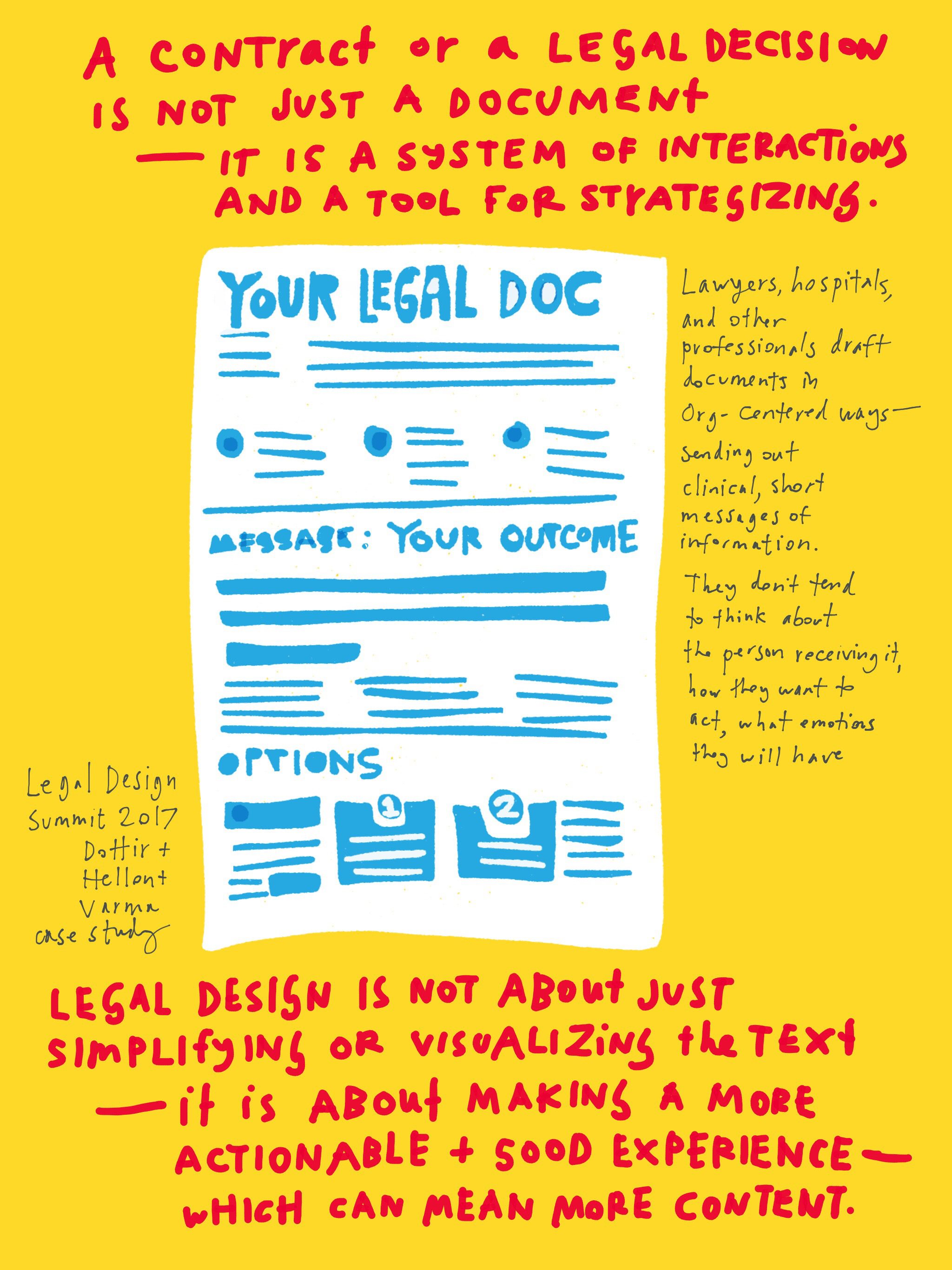

Based in the UK, we have been working with some US firms for a while to introduce a more European design style with better layout, structured text, white space and diagrams.

Much of the material coming from the US lawyers was text heavy, with the cliched images of gavels, pillars and court etc. Pitch documents were judged by weight! But this is how lawyers have been taught in law school – so good communication skills, including design needs to get onto the syllabus.

Once in-house counsel started complimenting the lawyers on their great materials – because good presentation made it easier for them to share with their non-lawyer colleagues – we started to get some real momentum.

Just as lawyers need to adapt, designers need to adapt their approach with lawyers. It can be frustrating initially, and lawyers are intolerant of any sloppiness or I attention to detail ( an occasional trait of creatives) but A good working relationship can be really successful.

Asking what lawyers want is one side; you get a lawyers answer which goes deep into details with all specifics and exceptions.

If you ask further as a designer, why they want it and ultimately what they actually want is a different story. As the previous post mentioned: you have to show it to them, visual evidence 😉

That makes the design process longer and you have to be patient. Show don’t tell, teach don’t preach.

That my lesson after working for a law firm as a information designer for a year now…

Margaret,

A reason for this behavior for USA lawyers is that perhaps they are putting together complex ideas and arguments. So just like having law books and briefs spread out over the surface of a desk or table, they want to replicate that sort of experience? I always thought that the TED talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/blaise_aguera_y_arcas_demos_photosynth?language=en had some of that possibility in the document interface part of the presentation.

I also wanted to share that some of this “need” was possibly explained in an old article by Malcolm Gladwell – The Social Life of Paper. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/03/25/the-social-life-of-paper

Hold on. If your users need max information in order to do their jobs, it would be a bad UI design that does not give it to them.

Good design means building your product so that it does what your users need. Function over (but not excluding) form.

If you want to see good, lawyer-friendly UI design, check out Fastcase. It does a great job of presenting lots of information in a way lawyers need (and want) in an attractive package.

Sam, I think that Fastcase looks very good but remember that there is a business focus to that interface, to deliver case research information. I took the example that Margaret put forward as one that reflects deep analysis. So something “Watson like” may be necessary to do the logical connections and filtering to get to the “simpler UI”. – Jim